Hitoshi Nakazato One Man Show

Nov. 24 – Dec. 5, 1970

“… Each time I stand in front of Nakazato’s work, I cannot help but feel the strong impact of the plane which abolishes the illusion of which the paining of the past consisted and taciturnity, featurelessness, and moreover a rebellious convincingness.”

Ichiro Haryu, Japanese art critic, Wako University, Professor Emeritus (1925 -2010)

The Plane Rebels Against the Painting!

Ichiro Haryu

“As Painting is to Sculpture: a Changing Ratio” was written a few years ago by Lucy R. Lippard. Certainly, it looks as if the focus of interest is shifting to the world of the three-dimensional, rather than the two-dimensional. However, retaining faith in the possibility of two-dimensional, Hitoshi Nakazato has been persistently attempting to dismantle painting to its boundaries.

For a long time painting had been recognized to be the copy of nature. The further it faithfully followed nature, it could not help but become helplessly into the reach of picture-fiction or the artists’ exaggeration based on illusion. The moment this was realized, modern painters endlessly resolved and metamorphosed the object and finally reached the picture surface which did not not represent anything but equaled itself. For example, in the 1910’s Casimir Malevitch in the work in which a white diamond shape floats on the white denoted this extreme.

However, the picture surface, which does not represent “anything,” is a work which reveals strength and purity of material quality. After World War II, Yves Klein, by completely covering the canvas with one color, blue, and reducing the materialistic element of painting to a minimum, tried to make purely conspicuous the existence of mere space of illusion itself. What has been exposed here by the works of these two is the fact that painting consists of essentially three basic conditions: plane, material and act, and it can be said that a new synthesis of these is being sought.

Hitoshi Nakazato started from this abandoned and uninhabited region in which the conflict of painting itself has been laid bare. In 1960 he graduated from college and became an art writer of a local newspaper. While seeing the movement against the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, the student revolt and the coup-d’etat of South Korea through the teletype, he planned to study abroad, he says. Besides enrolling at American universities and studying printmaking and printing processes, he went to factories as an interpreter for Japanese industrial engineers and gradually his eyes were opened to system design. Especially his experience of studying in Philadelphia under Piero Dorazio, an Italian artist, formed the structural basis of his art concept. The fundamental thought of European Constructivism, from Malevich to Klein and Fontana, runs through Dorazio. A few years ago, when I met him in New York, I was asked to be in his class’s teach-in in Philadelphia. Furthermore, Nakazato clarified his systematic thought through Dorazio, on the other hand, he seems to be attracted to the life- concept of the American beatnicks and hippies and amended his art from the almost primitive or original point of life. As this, he, beyond painting, started to be aware of the new possibilities of the two dimensional.

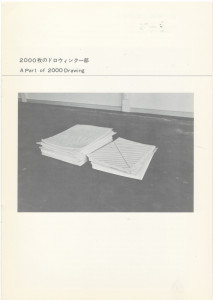

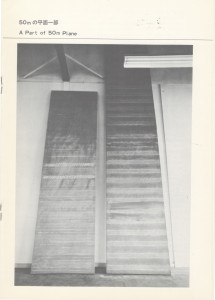

In order not to create illusion, the drawing-art is limited to the most simplistic and universal task in which he draws straight lines. On unprimed raw cotton duck or sheets of paper, using chalk, pencil and instant “sumi,” the straight lines, just as music scores, are drawn parallel sometimes, coming close then apart at other times, or smearing slightly.

There is a strong tactility of material and at the same time a fresh pulsation of the primeval action, also there is the humble respect of a craftsman who draws with the “sumi” liner. The space persistently is let open boundlessly, moreover, by the fact that “das Moment” of time in that the reality of act conceives. Each time I stand in front of Nakazato’s work, I cannot help but feel the strong impact of the plane which abolishes the illusion of which the paining of the past consisted and taciturnity, featurelessness, and moreover a rebellious convincingness.

This show is the first one man show in Japan for Hitoshi Nakazato, who came back two years ago. Having some doubt about the rental gallery system here, he has been seeking a different type of exhibition place, and did not have a one man show until now. His type of work that impels his own hypothesis to an extreme may not be easily accepted in Japan. Through I believe that this kind of work is the most important now. (Nov. 7, 1970)