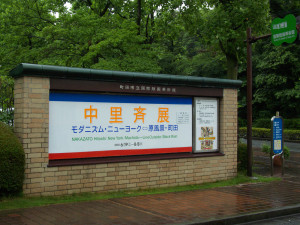

Hitoshi Nakazato Exhibition

From Line Outside, to Monadology, then Black Rain

June 19 – Aug. 8, 2010

“At a glance, there are no specific descriptions of everyday life in my work. So, I’d like to explain how my work reflects and responds to the life I’ve lived. To preface this explanation, there are many things, which motivate my artistic expression. Universalities such as intellect and emotion, objectiveness and subjectiveness motivate me as well, but what really inspire me are the dualities in the realities of my life.”

Hitoshi Nakazato 2010

“The other position that is unique to Nakazato is that he constantly paints and makes prints in parallel. Parallels are essence echoes of each other. As his linguistic duality similarly relate, “by expressing in one language, and confirm with the other,” the creation of the prints and painting mutually critique and respond to the other. The directness of the paint brush with its subjectivity and immediacy, contrast with the indirectness of the rollers via the intermediary plate with objectivity and systematic process, providing the fecundity of their coexistence in his two dimensional plane.”

Akira Tatehata, art critic, poet, Director of the National Museum of Art, Osaka

“I first directly got to know Hitoshi Nakazato as a faculty colleague at Tamabi in 1968 where Yoshishige Saito, the leading figure in the Japanese avant-garde, taught and invited me to teach as a full-time professor following Yoshiaki Tono and Yusuke Nakahara; we three critics were known as the “the big three”*1. To teach the studio classes, Saito invited an impressive group of working artists as faculty members starting with Jiro Takamatsu. Recent graduates Nobuo Sekine, Susumu Koshimizu, Kishio Suga hung out as though they were teaching assistants, and in their complete confidence and belief of Saito’s educational philosophy inquired into their own creative concepts and dismantled aspects of decor and sentiment from their works.”

Ichiro Haryu, former Chair of the AICA Japan, Director of Kanaz Forest of Creation, Director of Maruki Gallery for Hiroshima Panels, Professor Emeritus, Wako University

“… For an outsider, this is evidence in the work of a sensibility that emphasizes experience and enlightenment over theoretical knowledge seems manifestly Zen-like, as he superficially understands the concept, but this insight into Hitoshi’s working process inspires a paradoxical ambivalence. While it is exciting and gratifying to perceive an overarching philosophical spine to the work, the danger of naively exoticizing an American artist on the basis of his heritage is obvious, especially given the west’s history of cultural appropriation so aggressive it borders on imperialism. I suspect that for Hitoshi himself such external influences, as they would be for any good artist and craftsman, are at most unconscious influences in the studio. The body, trained by 10,000 hours of preparation, moves on its own.

The subtly playful curiosity that characterizes Hitoshi’s prints, drawings and paintings is also the mark of a born contrarian; his body of work, while paying homage to the past, also seems in endless debate with it. Hitoshi’s vocabulary of geometric and organic lines ultimately form a personal signature, merging his particular identity with his practice of experimentation. It is an elegant slight of hand: these complex and formal works serve as well as a massive self-portrait of the artist, created across time and space. ”

Matt Freedman, artist, writer, performing artist

“Nakazato only concentrates on creating a two-dimensional world that is separate from the actual world. Conscious that he is as a member of society, he has interests in landscapes and daily occurrences, politics and society, and international situations, which he incorporates onto the surface space of his work. ”

Koji Takizawa, curator

From Line Outside, to Monadology, then Black Rain

Curiosity is the source of our motivations in our daily lives. Curiosity has inspired the forward movement for human history from ancient times to the IT revolution in which we current find ourselves today. Curiosity feeds our imagination, which makes possible the tomorrows and the future to be. Without it, we would cease to imagine and tomorrow will not have been imagined when it comes.

Our curiosity questions our surroundings as we continue to gather information in order to expand ourselves. The information we collect may help us understand, or add perspective to a specific aspect of the issue, and in some cases it may even invoke an emotional response within us. There are those who strive to communicate these collected experiences through a tangible creation of expression. My method of expression is through painting, which is singular, and print making which is inherent in its multiplicity.

First, there is the duality between American and Japanese societies and cultures. America has been my home for half of my life, it’s culture can no longer be considered foreign to me. Yet, the fact that I continue to make art in America forces me to be acutely aware of my Japanese origins, much more than I would have felt it living in Japan, and more often than naught, I find myself caught between the two, which become the issues for my explorations.

Third is the duality that comes to the forefront of my mind in the studio. Painting and printmaking have a mutualistic relationship. One or the other takes the lead, and the other respectfully follows. Or one idea may go back and forth between the two and this synergetic bouncing of ideas helps me to arrive at a new destination.

The image making process can be described as this: one moves one’s hand over the chosen surface with a tool and what is drawn is sensed by the retina and transmitted to the brain. The brain responds and sends a message to the muscle of the arm, and the hand moves the tool again on the surface. The brain visually analyzes the consequent image again, which creates a cycle of neurological responses. The repetition of this cycle becomes the journey.

This cycle’s course is subject to instantaneous changes of mind or emotion, especially natural phenomenon or social situations of the outside world. At the same time, it is a journey that makes discernable the practicality of that which can be made tactile in visual terms. The directness and immediacy in this cycle can take the imagination to a higher level and extend the territory of our mind.

In printmaking, the various processes of the medium make it ideal for marking the journey. By working in stages, what is imagined is not always what is physically executed. As a result the expressions of the final result in the print medium has inevitable indirectness. Hence, printmaking is a journey that reveals this cycle in a more objective way.

The plate is first prepared, and paper placed on it and pressure applied; that printed image is reversed right for left, immediately giving it an indirect appearance and offering an objective view. When silkscreening, the image is not reversed, but the image printed through the screen has an instant detachedness.

Furthermore, printmaking leaves a proof for every step of the process. Leaving the proof behind, the process moves ahead. This proof is the record of the physicality of the particular steps in the cycles, which show the milestones of the journey. In other words, it makes it possible to see the path and analyze the direction of the creative process; the changes in sensibilities, and the individual inclinations in terms of something like habits and mannerisms. In other mediums, the new cycle is executed on top of the previous one, losing trace of what came before, and the analysis of the creative process is difficult. Thus, printmaking is the only medium that provides the stages of the process most concretely and objectively. For this reason, I proclaim, “Print making is image making,”

Printmaking as a vehicle

Traditionally, printmaking offers a variety of established methods of expression.

However, the printmaking workshop also provides unlimited opportunities to invent new vehicles for expression. They would take me to unexpected far places enabling me to look back where I had been before. I could switch to a different vehicle to reach a different destination. The places I might reach could be far beyond my expectation, a new territory.

From 1964, viscosity ink printing was my vehicle. Next, I rode on the large format of stone lithography in color. From 1968 through 1971 in the midst of the anti-establishment movement on campus, as a faculty member, I found myself caught between the demands of the students and the administration. In that political circumstance, it seemed to me that conventional printmaking was an outdated medium. I found myself attracted to working with the blueprint used by architects, and the newly invented copy machine. In the beginning of the 1970s, I returned to the printmaking studio to make a series of drypoint prints recycling used zinc plates, which gave the most direct result of the hand movement in printmaking. My next vehicle, I’ve continued to work with till this day. It is a deeply etched aquatint process that gives a rich black field using wax crayon to stop the acid bite. This process gives the effect of writing on the blackboard with a chalk, which began with an idea that the most productive image making could be on the backboard in a classroom. However, this idea had originated from the paintings for my one-person show at the Pinar Gallery in 1971 with white chalk on black background. Today, I use the liquid ground, which stops out the etching process of the acid from biting into plate.

Two-dimensional vehicle

In 1964, I went on to the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Fine Arts where I encountered the enthusiasm of the Bauhaus ideas, which had still not subsided, as well as the thriving Abstract Expressionism of the New York School. Penn was the place where the artists of that generation gathered in a truly open forum, which I interpreted as the sentiment toward the death of Jackson Pollock in 1956. The Color Field Painters such as my professor and advisor, Piero Dorazio said, “Color is the core of painterly expression.” Another artist in attendance, Barnett Newman had a work entitled “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue 1” (1966), and it was while he was painting this work that he visited my studio at Penn. I awoke to the rich possibilities of painting after being thrust into the eye of the storm of extraordinary environment and was exposed to many provocative paintings.

However, it became extremely difficult to make paintings in the latter half of the 1960’s in comparison to the first half. I found myself in the stalemate between the Vietnamese War and the hippie culture. To paint a canvas on an easel with a brush was considered an act of crime. I can clearly recall having a heated discussion with a friend about creating a work by pushing dirt and sand with a bulldozer.

The idea of abandoning painting on canvas was so enticing, I felt the realm of the avant-garde opening up in front of me with it’s endless possibilities, I made works spraying silver paint on a concrete plaza, and placing pieces of wood painted white in a natural environment. But, taking myself just outside of canvas, the effect of newness seemed to be too easily attainable. At the same time I felt that it’s artistic territory was being merely physically widened.

In 1968, I returned to Japan and spent three years with Japanese avant-garde artists and critics at the Tama Art University in the midst of the campus uprising and anti-establishment movement. At the Pinar Gallery’s one-person show in Aoyama, I showed a 100 meter-long work on canvas. Also, I showed a print 100 meters long that was a roll of the blueprint used for architectural drawings. In addition, I made prints using the copy machine, the brand new office equipment at the time.

In 1971, I returned to the University of Pennsylvania, Graduate School of Fine Arts, and continued my studio work in New York immersed in the artistic and cultural environment where Modernism gradually became passé. I attended conferences with Robert Venturi, an architect and the advocate of “Less is Bore.” In my own chronology, I call this era the “Less is More to Less is Bore” period.

Through these experiences, I began to question myself about what it was to defy existent art concepts, and have since decided to explore the possibilities of works on canvas, drawing on paper, and the two-dimensional media of prints. For this “Hitoshi Nakazato Exhibition” at the Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts, it is, of course, the prints that are the main focus.

Also included are a body of paintings on panels and drawings on paper. So, how does working in drawings and paintings affect the prints, or conversely the experience of print making influence the process of making drawings and paintings? From large-size canvases taller than I am to smaller panels, from large sheets of paper to thin washi paper, from the hard surfaces to more flexible ones, I’ve enjoyed this journey by switching vehicles of expression. All these works in this exhibition are the footsteps of this journey.

Line Outside

I borrowed Sengai’s motifs of ◯△□for “The Line Outside Series,” even though, these primary shapes became the conventional vocabulary of the Modernists since Russian Suprematism and the Bauhaus Movement, eventually becoming the modernist cultural cliché. I ventured to use them as the visual vocabulary in my work for their neutrality and simplicity, and as a paradoxical reference to the Modernist history.

I was offered a show by a museum in Israel in 1998, and created a series of works on paper, 30 inches height with a horizontal length of approximately 35 feet. One of the works is 50 meters long comprised of 10 pieces that are each 5 meters long, which is similar to the work shown at the Pinar Gallery. It was 36 inches high and 100 meters long in total, divided into more than 10 canvases and hung in two rows. In 1982, I exhibited 7 paintings that were 48 inches high and 10 to 13 feet in horizontal length at the Tokyo Gallery. In 2000, Hidenori Majima was at the University of Pennsylvania as an artist in residence from the Japanese Cultural Bureau and created some horizontally long works on paper for the ease of transportation. Since the condition set by the Israeli museum was to reduce the shipping expense of works, this format met the requirement perfectly. As I started to work on horizontally long paper, I was instantly drawn to the format that took me outside of the rectangular framework. I became absorbed in a long journey on this vehicle. Unfortunately, the show was not actualized due to the instability of the situation between Israel and Palestine.

And in the process, I discovered something unexpected and surprising. As I wondered about my deep involvement in this format, a memory flashed in my mind. It was a memory from as far back as I could recall, my original mindscape at the beginning of Showa Period (late 1930s) in the backyard of Narutoya, an indigo dying shop, my mother’s family home located along Machida’s main street. There were rows after rows of indigo dyed fabric horizontally pulled between poles and stretched by shinshi, thin bamboo sticks with needle-points on both ends, to flatten the width of the fabrics. I remember looking for my mother while running underneath these rows with hundreds of shinshi, which hung down creating reverse arches beneath the fabric.

Since 1962 when I left Japan looking for encounters with the avant-garde, I kept my focus consciously forward. It was the first time I found myself traveling back to the beginning of the Showa Period and traditional Japan. In this encounter I experienced, the collision of the avant-garde mindset and the original mindscape from deep within my soul, which was unknown territory, the line outside.

9/11

In 2001, I wanted to create a project to celebrate the beginning of the new century. I decided to make as many paintings as the number of the years and entitled it “The 2001 Project.” This project began with the “Line Outside Series.” But not long after starting the project, the world witnessed the 9/11 terrorist attacks. 2600 victims were lost in the World Trade Center in New York and it was difficult to work in the acrid air in the days that followed. I asked myself what it meant to work everyday in the studio, and became skeptical as to what I could do to contribute to society. Of course, there was no scheme behind the concept of “The Line Outside Series” using the very limited vocabulary to deal with 9/11, and in fact, I was not sure whether the incident should affect the direction of the work or not.

To create two-dimensional works, to make paintings, is what I have been doing since I was a child, and I continue to do so to this day as an instinctual part of myself. However, there were three times in my life when I clearly recall not being able to paint

The first time was when I believed that my life would end short under the air raids during the second world war and the hunger in its aftermath. This faded away as society became more stable. The drawings I made, with the small stock of Sakura crayons purchased before the wartime shortage, received ‘unsatisfactory’ marks in elementary school, and this bothered me for a very long time. Recently, I went back and found those drawings to take another look, and discovered that they were crying out for something with their rough touches.

The next time was the period, 1968 to 1971, when I found myself asking what it meant to be an artist under the criticism from radical student sects of the anti-establishment movement. It was only possible to overcome through an encounter where I found the justification for making art. Furthermore, this experience contributed thereafter to my studio work and the decision I made in how to pursue my artistic career. That encounter was with Carl Andre, a sculptor from New York, who was invited by Yusuke Nakahara to one of the off-campus seminars during the Tama Arts University student uprising. Ichiro Haryu asked him, “Is there a possibility for art to ever become obsolete?” What I understood from Andre’s response was that “The studio is the place for imagination, the fountainhead of history.”

Monadology

Counting art works by number seemed to be a simple task for “The 2001 Project,” but proved to be difficult. Counting a large canvas work and a small drawing as equally as one may conflict in comparison to the time spent on their execution. However, in the crisis situation after 9/11 and self-imposed pressure, I proceeded by preparing 500, 19 X 24 inch panels for the practical solution of its availability and the storage of the finished works. As the project progressed, the name of the project, which started with “Line Outside Series” had to be changed, with the shifting of my interest to a newer idea.

The prepared panels, started to play a role in the development of a new concept. As the work progressed, it became gradually apparent that the aspect of the task I needed to focus on was to create tension utilizing the limited chosen pictorial vocabulary of primary shapes. This would give it the reason to exist as a work. The objective itself was to create a micro-cosmos on a pictorial plane. The next thought I had was that the cosmology of the Greek philosophers in understanding the world was in a sense their cosmic-scape paintings. Moreover, the two dimensional micro-cosmos of the “Line Outside Series” that consisted of primary shapes could be the embodiment of Gottfried Leibniz’s (1646-1716) Monadology. It is said that Monado is nothing but a simple substance, which enters into compounds. Monados are the real atoms of nature or building blocks of our world.

In late 2004, the “Monado Series” was added to “The 2001 Project.” Changing the title of the series made me realized that there was no reason to stay with Sengai’s vocabulary of the three primary shapes. Thereafter I freed myself by choosing and inventing other simple elemental forms to continue searching for newer painterly territory.

Black Rain

In the summer of 2007, I visited the Hiroshima Memorial Museum where I read some of the U.S. Government documents displayed there about the Manhattan Project. The following year, a Hiroshima gallery near the epicenter of the bombing invited me to have a one-person show with Hiroshima as it’s theme opening on August 6, 2009. I began by doing research, gathering information such as photographs of Hiroshima before and after the bombing, paintings made by the victims, the Atomic Panels by the Maruki’s, even a map of Hiroshima, and I went through them many times.

By spring of 2009, I’d completed 100 panels of the “The Black Rain Series.” And, I was asked by the Pagent : Soloveev Gallery in Philadelphia located near Independence Hall to exhibit opening on July 3rd, the night before Independence Day. And the following October, “Black Rain II” was shown at the NY Coo Gallery in New York. Both shows consisted of 19 by 24 inch panels to be seen as a continuum, one frame after another as if a movie reel.

Back to Serigaya

One day in 1990, I found a thick catalog in my mailbox at the University of Pennsylvania where I’d taught since 1971. It was signed Ruth Fine. An alumnus of The University of Pennsylvania, Ruth was two years ahead of me and at the time the curator of prints and drawings at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. The catalog was for the opening of The Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts, which she curated: “Gemini, Collaboration between Artisan and Artists.” She had somehow placed the catalog in my mailbox after returning from Japan. From then on, an idea of exhibiting my work at the museum grew. I am grateful to have this exhibition here where I grew up come true, and I thank the many people who made this exhibition possible.

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the cooperation of those gave support.

Hitoshi Nakazato

February 1, 2010

The Art and Life of Hitoshi Nakazato

Although I am not directly familiar with Hitoshi Nakazato’s upbringing, on the occasion of his first retrospective at the Machida City Museum of Graphic Arts in the western region of Metropolitan Tokyo, the fact that he chased rabbits in the forests and fields as a child, and during and after World War II hunted for crabs and snails in the stream in Serigaya where the museum now stands bears significance. His father worked for the national railroad which as a government run enterprise was known to be a reliable organization before it was broken up and privatized by Prime Minister Nakasone [1987], and his mother’s family‘s indigo dye shop on Machida’s main street left something indelible in his mind in aspects of dyed fabrics and colors. However, what stuck his spiritual core as an artist of expression in memory and experience can be nothing other than the Christian consciousness that touched him at Obirin Gakuen which evolved so quickly as an institution in the Machida area.

Hitoshi Nakazato graduated Obirin High School and entered Tama Art University (Tamabi) as an oil painting major. From his desire to explore studio processes and experiment with expressions, after graduating from the University, he went to study in the U.S. as a graduate student in 1962 first at the University of Wisconsin and then at the University of Pennsylvania. This physical shift to the U.S. can be understood through the enormous transformation that he experienced while he concentrated on printmaking. Here is a list of some issues related to what he underwent in no particular order: 1) his dissatisfaction with the placement of internal images as strip specimen, 2) his interest in the so-called American hardedge abstraction which lead to an intense fascination in the quality of paper and color in printmaking, 3) his denial of delicate surface-treated commercially viable expression and his empathy towards the free-spirited young people who became hippies in America in their opposition against Vietnam War, 4) his doubt in the traditionally accepted norm of what were considered prints in the advent of office copiers that were becoming available, 5) his Black Rain series shown in one-person shows in New York and Philadelphia galleries last year which resulted from his visit to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and seeing the personal effects of the bombing and the documents related to the American Government’s Manhattan Project which relate back to his own experiences and color abstractions.

I first directly got to know Hitoshi Nakazato as a faculty colleague at Tamabi in 1968 where Yoshishige Saito, the leading figure in the Japanese avant-garde, taught and invited me to teach as a full-time professor following Yoshiaki Tono and Yusuke Nakahara; we three critics were known as the “the big three”*1. To teach the studio classes, Saito invited an impressive group of working artists as faculty members starting with Jiro Takamatsu. Recent graduates Nobuo Sekine, Susumu Koshimizu, Kishio Suga hung out as though they were teaching assistants, and in their complete confidence and belief of Saito’s educational philosophy inquired into their own creative concepts and dismantled aspects of decor and sentiment from their works.

In December 1968, the student protests occurred at Tamabi as they had at other universities. I became a full-time professor that April while I served as a commissioner of the Venice Biennale. With the other commissioners, a letter was issued to protest against the police confrontation with the people and students who rushed to the Venice Biennale after the unsuccessful “May Revolution in Paris” that ended with the re-election of President Charles de Gaulle. Under these circumstances, I was not able to be at the University during the first semester.*2 The student uprisings in other schools such as Tokyo University and Nihon University occurred almost half a year before Tamabi so the delay seemed a bit off season.

Tamabi’s Kosei Hori and Naoyoshi Hikosaka encouraged art student peers of other universities and colleges that rather than the Zenkyoto*3 movement, reversed Immanuel Kant’s subjective aesthetics “if art can only be captured subjectively, then that is the main battleground.” I have deeper interest in “Bikyoto.”*4 At this time, Nakazato as a full-time faculty at Tamabi intermingled with the Japanese avant-gardists that centered around Yoshishige Saito. Nakazato had a one-person show I curated at the Aoyama Pinar Gallery where he showed his 10 large-size horizontal canvases in two tiers (100 Meter Painting). Yusuke Nakahara as the commissioner for the Tokyo Biennale [1970] invited, among the foreign artists, Carl Andre, a former railroad worker who placed railroad ties on the floor of the exhibition space for the visitors to walk on. This plain logic and directness became the focal view included in “Bikyoto.”

Nakazato’s return to the University of Pennsylvania in 1971 opened new possibilities for his art and life. While keeping his studio in New York, he aimed toward the ideals of one of the founding fathers of immigrants, Benjamin Franklin. By rooting the identity of individuals in their art work, he created a space to realize social communication by reconsidering and transforming the scope of the curriculum at the Graduate School. In addition to the three majors of painting, sculpture, and printmaking he newly established a mixed media major, as well as clay and digital technology studios, and also hosted visiting artists, recipients of the Japanese Government Cultural Bureau’s Artists Abroad Grant and those from other countries. He organized exhibitions within the university and incorporated notices and articles in departmental catalogs and newsletters. This demonstrates the multidimensional possibilities of education, which Nakazato implemented. It is no wonder that as a leader in educational transformation, he was appointed to serve as departmental chair of the University of Pennsylvania, Graduate School of Fine Arts in the 1990s.

Although he retired from the University in 2006, his sphere of influence could be seen in the exhibitions held in the spring and autumn of the following year on campus and in the city of Philadelphia with the works of his ex-students and visiting artists. Nakazato continues to maintain his base in New York and Philadelphia, and in his mature years continues to be productive and provocative.

In his private life, after parting with his American wife, Nakazato remarried a professional simultaneous interpreter of independent means who was born in Japan and raised and educated in the U.S. I have known her from the time that she taught English at the Tokyo School of Art and translated art related essays and articles. Nakazato maintains a close and mutually cooperative relationship with his better-half.

Ichiro Haryu

Translator’s notes:

*1 In the Tokugawa Period, the three branch houses of Tokugawa rivaled to have their sons adopted into the main Tokugawa household to become the next shogun after the death of the Tokugawa shogun without an heir. The terminology 御三家 (gosanke), translated “the big three” was coined to describe the influential three-some Japanese critics.

*2 The academic year in Japan begins in April, so December would be in the middle of the second semester.

*3 Zenkyoto 全共闘is the abbreviation for 全学共闘会議 (zengaku kyoto kaigi) or literally university united front, a group of universities throughout Japan that formed a protest group against the establishment.

*4 Bikyoto 美共闘or literally art united front.

Translation: Sumiko Takeda / Editing: Gene Nakazato

Hitoshi Nakazato’s Triumphant Position

When describing art, we keep in mind when the work was created and to which –isms it may be ascribed. Comprehending the work’s place in time and stylistic classification are prerequisite to understanding the work itself. What is more important than those two, I believe, is knowing where that work was created. Most artists of prominence have an instinctive awareness of their place, literally and physically. The social and cultural environment under which they work affects their destiny by choice.

Hitoshi Nakazato writes, “At a glance, there are no specific descriptions of everyday life in my work. I’d like to explain how my works reflect and responds to the life I’ve lived. To preface this explanation, there are many things which motivate my artistic expression.” This ability to draw from a multitude of inspirations is truly revealing. Nakazato’s scrupulous abstractions reflect nothing endemic at first sight. To him, imagery is a universal language and in his work there is no indication of the natural surroundings where he was born and raised in Tokyo. There is no way to grasp his experiences at his campus that witnessed uprisings that assaulted Japanese art universities, in New York where he keeps his studio, or in Philadelphia where he taught for many years. But he insists that his work ‘reflects and responds to life.’

Then how do the universal language of imagery and the environment in which he placed himself as an individual relate. To pursue a universal criteria, why did he leave Japan for America as the place to do his work when he did? What meaning does his native culture, University of Pennsylvania, and New York hold for this artist?

Simply stated, expatriating himself creates a multi-dimensional layering of cultures. This is the decisive foundation of Hitoshi Nakazato’s universe. This is not by any means a paradox. Expatriotism is not a disassociation from the past, but instead means unavoidably encountering differing cultures. Nakazato‘s critical perspective of the two cultures guide him to a new language that is neither eclectic nor accumulative, but raises possibilities for expressions which only this artist is capable of doing.

A specific example is a series entitled “Line Outside.” In the first half the 1960s when Nakazato first went to the U.S., New York Abstract Expressionism was beginning to wane and its formalistic painterly space came into question, a time when Pop Art and Minimalism were just emerging. Nakazato found a way to respond to his sensibility in the straightforward colors and configurations of Color Field Painting, which were in a wide sense influenced by Minimalism.

The “Less is More” concept of the times ultimately arrived as huge single color fields, but to Nakazato “less” alone did not fit his ticket. As an artist who also emphasizes the importance of drawing, Nakazato saw the concept of “less” as a means to explore the possibilities of the line. At times, geometric straight lines that have the nuance of hand-drawn lines are placed on the color surface of the canvas. And what is to be noted is the same simplicity recaptured, not with inorganic hardness, with the soft commonality of Japanese and Asian qualities.

Started in the latter half of the 1980s, the “Line Outside” series unmistakably demonstrates his multi-layering of cultures. While trying to go ‘outside’ the notion of lines as defined in Western paintings such as dividing lines, contour lines, and independent lines, Nakazato explored other possibilities while not denying the line itself, eventually on his own accord he came across upon Sengai’s Zen painting. The onomatopoeia of Chinese characters, Line Outside = Sengai (線外=仙崖), while looking outside the line of Western and American Modernism, Sengai of his homeland was revealed. This bears the humor of his critical insight and provides a view of the humanism (人文) (in other words, another pun: literary man style tradition: 文人) that lurks behind.

To the witty picture of only ◯△□ painted by the Zen monk in the latter part of the Edo Period, Nakazato rediscovered in his American environment the Modernist visual language of his own native culture that came far before Suprematism, Minimalism, and Conceptualism. Yet to call that Modernism is post facto, and where he finds himself is the common ground of multi-dimensional cultures and his investigation of the line is its position within a larger horizon. In actuality, the ◯△□ that appears on his paintings are unlike the dryness of Sol Lewitt and Kenneth Noland, conceived with a delectable touch of humanism. This softness in not only evident in the lines but can be noted in his sense of color as a refined colorist.

The other position that is unique to Nakazato is that he constantly paints and makes prints in parallel. Parallels are essence echoes of each other. As his linguistic duality similarly relate, “by expressing in one language, and confirm with the other,” the creation of the prints and painting mutually critique and respond to the other. The directness of the paint brush with its subjectivity and immediacy, contrast with the indirectness of the rollers via the intermediary plate with objectivity and systematic process, providing the fecundity of their coexistence in his two dimensional plane.

Hitoshi Nakazato’s triumphant position: viewers of this retrospective exhibition will certainly find themselves impressed by this discerning and vivacious world.

Akira Tatehata

Translation: Sumiko Takeda / Editor: Gene Nakazato

I Got to Know Hitoshi

I first got to know Hitoshi Nakazato in 1994 in the midst of the final critiques for the fine arts graduate students at the University of Pennsylvania. These critiques were and are grueling affairs for all concerned; three consecutive eight hour days of very public dissections of the work of every student in the program by a panel of professors, visiting artists, writers and curators. One by one each student in sets up a semester’s worth of art in front of the critics and all the other students, then stands back and listens for half an hour to the faculty debate the merits of their production. Very few students emerge unscathed, and that first weekend more than one young artist was reduced to tears. It’s almost as traumatic an experience for the younger faculty. Each speech is a perilous venture into the unknown, as critics’ comments are analyzed as skeptically as the critiqued work. I was doubly impressed, therefore, by the stabilizing presence of Hitoshi in the midst of this fraught environment. Gracious, intuitive, generous and utterly original in his comments, Hitoshi was a consistent source of light and calm in a roiling environment. I have learned more from my experience teaching alongside Hitoshi and his colleagues than I did in all my years as a student.

I continued to be impressed by Hitoshi as a teacher and a colleague over the years that followed. Steady and determined, he pursued his vocation as a teacher with an unwavering faith in his own values and an unshakable commitment to the students’ needs. It was Hitoshi’s decency that struck me first about the man, but that quality turned out to be a relevant introduction to the work of the artist. If rigorous abstraction have an ethical dimension, then Hitoshi’s work is profoundly ethical both in content and in practice. His innovations as a printmaker gave form to his contributions as a teacher and his remarkable work ethic in the studio made him an inspiring and demanding role model for generations of adoring students. I am struck by the words of his student John D. Woolsey, who studied with Hitoshi in the early 1970’s, “(studio practice) became almost a Zen meditation: the feel and heft of properly soaked paper, the right heat of an etching plate before wiping it, the silky feel of properly wiped in. ‘You haven’t wiped your plate right’ we would hear from 20 feet away. ‘How do you know?’ we would respond. “I can hear.”

Each time I visit Hitoshi’s studio I am reminded all over again what it means to be an artist in the most fundamental and imposing sense of the word. His commitment to craft certainly provides one dimension of this personification, but more profoundly, Hitoshi’s artistry lies in the inextricable connection between his craft and his larger moral vision, and his example of a life fully dedicated to the uncompromised pursuit of a vision of beauty. His huge work studio is bisected diagonally by an extraordinarily long worktable. Stacks of canvases are intricately arranged on shelves and rolling carts placed all around the room. File drawers and boxes are filled to the brim with cardboard folders, each in turn stuffed fat with prints and drawings and paintings interwoven between glassine sheets. To sit in Hitoshi’s studio and pour through the rich and bountiful effluvia of his restless imagination and a tireless hand is to meet with the evidence of a career spent erasing the boundaries between thought and action, work and being.

I am fascinated by the elegant circuitry of Hitoshi’s creative imagination. One sharp reductive image leads to another, which leads to another, then another, then another. Sometimes the interposing logic is obvious; sometimes it springs to view only after the artist casually provides a hint or two. A square leads to a circle, leads to a triangle. A rectangle perches on a square, stands before a rectangle. A red form repeats itself in yellow, black, and green. A series of crescent forms climb a vertical line on one sheet, then in the next iteration suddenly flip and become a horizontal dangle of vegetal pods. In no other artist’s work do I see the logic and potential of the print process play out as rationally yet as imaginatively, bountifully, and exuberantly as it does in Hitoshi’s prints. Experimentation and fecundity are raised in his practice to the level of an esthetic philosophy. No form resides as the final word, and no image can be considered in isolation; each inspires speculation about the next contingent manifestation. Looking through Hitoshi’s print series I always find myself silently picking out a favorite or two and imagining the pleasure I would derive from having the opportunity to contemplate them on their own. More precisely, I try to imagine the effect of a single print of Hitoshi’s on a hypothetical viewer who, encountering the work without foreknowledge of all its cousins, could accept it as the preferred distillation of the artist’s vision. I imagine that print would be utterly satisfying to its observer. Each one of Hitoshi’s pieces is fully capable of leading an independent existence. Each one is a complete and self-sufficient statement. But that is not how I choose to think of them. I see them all, the prints, the drawings, the paintings, the studio, the shelves and the boxes and crates and rolls of work; the thousands of painting and print and drawings as inseparable form the man himself, the entire inventory a massive masterwork, a contemplative explosion of creativity. For an outsider, this is evidence in the work of a sensibility that emphasizes experience and enlightenment over theoretical knowledge seems manifestly Zen-like, as he superficially understands the concept, but this insight into Hitoshi’s working process inspires a paradoxical ambivalence. While it is exciting and gratifying to perceive an overarching philosophical spine to the work, the danger of naively exoticizing an American artist on the basis of his heritage is obvious, especially given the west’s history of cultural appropriation so aggressive it borders on imperialism. I suspect that for Hitoshi himself such external influences, as they would be for any good artist and craftsman, are at most unconscious influences in the studio. The body, trained by 10,000 hours of preparation, moves on its own.

The subtly playful curiosity that characterizes Hitoshi’s prints, drawings and paintings is also the mark of a born contrarian; his body of work, while paying homage to the past, also seems in endless debate with it. Hitoshi’s vocabulary of geometric and organic lines ultimately form a personal signature, merging his particular identity with his practice of experimentation. It is an elegant slight of hand: these complex and formal works serve as well as a massive self-portrait of the artist, created across time and space.

This continual oscillation between identity and form began early. Hitoshi explained to me how he was struck as a child by the symmetry of the Chinese characters that compose his name-a symmetry that made his name stand out in the posted class rankings and so marked him for special distinction if he rose to the top of the class, but also special humiliation if he sank towards the bottom, as also, inevitably, sometimes occurred. Perhaps that fascination with abstract line and textual meaning helped draw him to the work of the Zen master monk -artists of the past, especially the Renzai practitioner Sengai, whose elegant, witty and visionary drawings from the eighteenth century anticipate the achievements of contemporary movements in abstract and conceptual art by fully 100 years. Sengai’s depictions of iconic triangles, squares and circles were drawn long before the Russian Constructivists, Bauhaus designers and post modern recyclers threatened to turn such forms into trivialities. Hitoshi has deconstructed this master of the odd confluence of the distant and the profound, the modern and the ironic, and internalized him into his identity and his practice. A homonym for Sengai, which translates to “Monk on a Cliff”, is “Line Outside” a term and a position Hitoshi takes into his own practice. For such a master as Sengai, the notion of separating life from philosophy, from work, was unthinkable. And so it is for Hitoshi.

Hitoshi notes, in the essay he prepared for this catalog, that there were only three times in his long and productive life when he found it difficult to produce art. His first crisis came as a young boy in the waning days of World War Two and in its immediate aftermath, when life itself, much less art, seemed not to be a reliable commodity. A second came thirty years later, when as a teacher in Japan caught in the vortex of the political convulsions of the 1960’s, he was forced to swear to adhere to absurd esthetic choices in the name of abstract political causes. Art seemed a weak gesture in the face of such consuming anger. Finally came the World Trade Tower attacks, within eyesight and drifting winds of the artist’s studio. Ironically Hitoshi was then the midst of a typically atypical project-he was attempting to produce 2001 paintings in 2001- when this brutal attack on culture and civilization as he knew it derailed him. Again, briefly, making art was a hard choice for an artist for whom art was not a choice at all.

Hitoshi Nakazato built a prolific career in enlightened domains, but he has also seen first hand the fragility of such privileged systems. The final balance though tilts toward life, for his life and body of work embodies the peculiar world-creating beauty that animates our spirits and flows from our hearts into the world through the work of our hands.

Matt Freedman artist, writer, performing artist, visiting artist, University of Pennsylvania, School of Design

Restoration in the Rights and Amplification of Image

—A Memorandum to the Hitoshi Nakazato Exhibition

“NAKAZATO Hitoshi: New York/Machida—Line Outside/Black Rain” was planned by the artist himself. Many artists who are in the present progressive tense, working and holding exhibitions do so, and Nakazato did not adhere to the format of standard retrospectives. None of his work from the 1960s, when he first began to show, are included, and even the number of pieces from the 1970s to the 1990s are few in number; 6, 18, and 4 respectively for each of those decades. Although a portion of them is placed nonchalantly into the framework of this show, the majority are those from after 2000. This one-person exhibition is about Hitoshi Nakazato’s current expression and artistic activities, characterized to show the concepts behind them.

By showing a handful of works that are clearly from ‘the past,’ Nakazato provides insights into the changes in the content of the expressions for each of the periods. By doing so, he affirms his expression in the present progressive tense conveying the ‘contemporary-ness’ of these series. At the same time, he suggests the issues and concepts that underlie his work from the 1970s are just as meaningful today. It is through understanding the changes in his expression that one can get closer to the crux of his expression and his concepts.

The work to be referenced for this purpose is the “400 Meter White Line” in the corner among the “More is More” series. Although this work was created in 2005, it was a remake of the “100 Meter Canvas,” shown in 1971 at the Aoyama Pinar Gallery located in Tokyo, so it can be discerned as a work of the past. In the 1960s, Nakazato was drawn to Minimalism, Primary Structure, and Conceptual Art that followed, in the New York art scene. By setting himself apart from making subjective and sensory images to consider the essence of two-dimensionality, he chose the extremely simple act of drawing a straight line on a flat surface. “400 Meter White Line” incorporates the vestige of such thoughts, and in comparison to the work he is currently pursuing, is one the pieces that is essential for this exhibition.

In order to clarify Nakazato’s thoughts and changes in his work from then on, I’d like to put on record his own words from the early 1970s:

Currently, the cruxes of the issue in my work are definitely not for illusion sake, nor for appearance of material, but the flat surface itself and the exploration into the intrinsic structure of two-dimensionality. And I limit myself to the simple act of drawing a straight line on the surface plane as the most universal act of expression.1

There was a time when I totally lost interest in painting images. In which case, what remained was only to draw lines and fill a surface with paint. The first of the series I worked on with this idea was about 10 years ago, a series with only lines.2

And, Nakazato’s change in thought is clear from his statement below in the latter half of the 1970s:

I’m thinking more about images. As a matter of fact, painting is about creating images.3

In this statement, his interest in imagery that he at one time denied is expressed consciously. That in itself may be discernable to anyone. This change in thought affected his work. However, the issue then becomes how the imagery evolved in his work. That is the critical issue on hand. And what must be noted is Nakazato saying, “to make imagery.” These words are about creating imagery by drawing lines, planes, or shapes and painting colors onto a blank surface. It is also for the viewer to find some kind of imagery, to perceive some shape that can be called a gestalt image on the flat surface.

What characterizes Nakazato’s work of the latter half of the 1970s is his adamant affinity toward minimalistic image making by limiting himself to the most basic elements. Nakazato only gave himself lines and geometric shapes and monochromatic colors which are the most basic elements for expression, support materials such as canvas and paper, and the simplest tools to draw and paint. Specific imagery that promotes communication such memories, emotions, and motifs are completely and inherently precluded. The making of an abstract work with the minimalist inclination is a result of this stark condition he set for himself in his image making. The imagery that was created can only be called gestalt. But what Nakazato sought were works with “a strong gestalt image” that would impose “tension.” 4

In printmaking, various tools and materials are utilized in its complex processes but Nakazato’s the basic thinking remains the same. The etching entitled “Kerr,” and “AE” and “AI” among the “Aquatint” are the result of such processes. Another example of this fundamental thought can be found in his work on paper from the 1980’s to the current—the “Line Outside Series,” “Air Catcher,” “Pantone Series” grouped as “Relief Inking” and “300 lb paper” respectively. To be noted, these works were unmistakably made under conditions less severely limiting compared with those in the latter half of the 1970s. The colors and shapes, drawing and painting techniques, structure, and selection of materials are confirmations of the release from his earlier constraints. One wonders if even the imagination Nakazato had restricted from him earlier in image making is being introduced.

Despite such changes, Nakazato only concentrates on creating a two-dimensional world that is separate from the actual world. Conscious that he is as a member of society, he has interests in landscapes and daily occurrences, politics and society, and international situations, which he incorporates onto the surface space of his work of his work. The following comment expresses Nakazato’s awareness:

The works that make up the major portion of the show in 1987 were made while listening to the “Iran Contra Hearings” on television in the loft. From the loft window I could see the police arresting crack cocaine dealers. This is the best backdrop for painting… Edward Fry who came to my loft late at night continued to emphasize the significant criticality of society and politics in art. I cannot say that his words gave my work a specific direction, but it provoked me in many ways.5

The “Enron Series” was triggered by the Enron Scandal which was a result of bankruptcy due to compliance infringements and other violations and the “Sand Print Series” was made with the sand purchased at a bargain when Woolworth, the American 5 & 10 cent stores, closed its doors due to bankruptcy. Both tell us that Nakazato’s creative process comes from his intuition toward social issues and incidences. Such propensity unfolds in his works reflecting political concerns as well, “Homage to the Lithuanian People” and “Homage to the African National Congress,” and works that may recall landscapes “Monado: Winter Curves” “Monado: Summer Line” are examples of this.

And more recently, Nakazato who condoned imagery of the actual world shifted to the theme of Hiroshima as if he were emotionally drawn to do so. Also, combining imagery inspired by the ◯△□ painted by Sengai and the monology of Leibniz, he created the “Folded Black Rain” Series, which amplifies imagery.

Although Nakazato does not incorporate excessive imagery in this exhibition in comparison to his stoic works of the 1970s, the imagery is profuse. But that too is a process in the thought behind image making in two-dimensional work.

Bibliography

1. Hitoshi Nakazato. Mizue Vol. 804– Special Issue 1972 “The Basis for Art Making” January 1972, Tokyo, p. 48.

2. Hitoshi Nakazato and Fujieda, Teruo, Mizue Vol. 897-Contemporary Dialog Part II – 4 “Surface Plane and Space” December 1979, Tokyo, p. 72

3. Ibid, p. 77

4. Ibid, p. 77

5. Hitoshi Nakazato–Twenty Year History Arukanshieru (Arc-en-Ciel) Arts Foundation, Tokyo, June 1987.

Translation: Sumiko Takeda / Editing: Gene Nakazato

Explanations of Projects

I. Embossing

I began making prints in 1962 in the print workshop at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. At the time, the local Milwaukee beer breweries had switched their beer cans from tin to aluminum, resulting in abundance in the surplus of coated flat tin plates at the studio. Drawing with an etching needle over the Miller brand coating, I processed endless numbers of them in the etching solution to create the intaglio plates.

At the same time, to prepare for lithography printing, I ground the old litho stones with clear images still visible from commercial use by the local printing companies. I excelled in lithography. In 1963, I printed an edition for Orest Velesky on the occasion of the USSR Graphic Art Touring Exhibition in the U.S. From 1964 – 1966, edified by the works at the Tamarind Institute Lithography Workshop (established in 1959), I created large-scale lithographs. And, in 1964, I assisted Kaiko Moti (1921-1989), one of the inventors of the multi-color single plate at the Atelier 17 in Paris where Stanley Hayter presided. During the time, I was able to master the technique and produced many works.

The works displayed here is the earliest of the works in this exhibition created when I returned to Japan from my study in the U.S. It was created right after interacting with Italian artists Diero Dorazio (1927-2005) and Angelo Savalli (1911-1995), and German Otto Piene (1928-) where the influence of the Zero Group and Arte Povera is noticeable.

II. Minimalist Vision

Viewing a beautiful sunset, saying to a friend, “Beautiful, isn’t it.” to communicate a mutual feeling. The friend responds, “Yeah” and the mutual feeling is consummated. Or riding in a subway, seeing the person sitting on the other side yawn and yawning unconsciously. Even in such situations, communication between people happens. But does such all-too-common instinctive communication occur between people and art?

For example, when thinking about the title for a work, I look at the league standings of the MLB in the sports section of the newspaper and see “Kerr,” the name of a player. And without any reason, I tell myself, “That’s it!” There have been three major league players named “Kerr” in its history, and among them, John Kerr was born in the same year as I was and passed away in 2009. Although there is no specific relationship between his name and my work, I feel that a communication of some kind occurred.

By eliminating the process of image making through drawing from nature, psychological description, personal memory, habits, and emotion, what could my work communicate? My pursuit is to come up with images that might engage in a communication with the mind of the viewer.

III. Enron Series

Enron with its 2,200 employees recorded the highest profits in corporate history in 2001 in businesses ranging from electricity, natural gas, communications, and pulp for paper manufacturing. However, the following year, due to their fraudulent bookkeeping and poor financial handling, and unethical business practices in developing nations became troubled and declared bankruptcy, raising many questions on the whole about American corporate management practices. To destroy evidence, documents were shredded. The Enron Scandal provided a hint for this series.

IV. Relief Inking

This series is based on the concept of “Process as Imagemaking.” First, drawings were made using wax crayon on a number of different size plates and then etched deeply in the acid mordant. For printing, different colored inks were applied with brayer on each of the different plates, which were assembled on the press on the bed to be printed. In this process, inking was only on the raised portion of the plate to make it easier to clean and to change color. The printed image was formed by the placement of the different plates on the press. The image is created through the choice of colors and combination of the plates.

V. 300 lb paper

These prints utilize the rigid support of the 300 lb watercolor paper. The screen print incorporates acrylic drawing and sand. Its physical presence and two-dimensional breadth were the goals. I place these works on paper on par with works I have done on canvas.

VI. Air Catcher

Frustrated by rectilinear paper and the limitations it sets on the size of the image, these, works are cutouts of motifs from works on paper that are installed on the wall itself. To accentuate the circle, triangle, and square, the pieces float from the wall catching the movement of the air in the surroundings.

VII. Sand Painting

Playing with sand in the sandbox stirs one’s imaginations. These works also began with sand play. The sand that’s used was purchased from the aquarium department of Woolworth, the American 5 & 10 cent store chain, when their stores closed after its bankruptcy.

VIII. Pantone Series

This is an offset lithograph series made at the Brandywine Workshop in Philadelphia. One set includes 350 prints in variation and only two sets, 2 editions, were created. This project is made with a combination of 5 aluminum plates and 5 colors. Pantone is the brand name of the ink that was used.

IX. Screen Print

While grinding the stone plates used in lithography, the abrasive sand and water combine on the ochre colored limestone surface creating images endlessly. This series came about from the thought of capturing these images that unfold in the process on paper. The idea came from the kira-zuri technique of Ukiyo-e in the Edo Period; powdered mica was applied and fixed on some areas of the image. I applied this idea to screen printing.

X. Aquatint

Sprinkling powdered resin evenly on a copper plate, heating it to make it adhere, and then drawing on it with wax crayon. When the plate is etched in acid, the portion that was drawn with crayon remains unetched. It is then inked to create an intaglio print. The solid blackness of the background is through the effect of the mezzotint method. The movement of the drawing is a result of crayon drawing on the litho plate. This is a process I’ve used repeatedly over the years.

XI. More is More

These works were created to get out of the rectilinear framework of paintings, and they could be rolled up to fulfill a request for convenient transport. While painting these works, I asked myself why I was making such elongated works. Then the memory of my original mindscape flashed in my mind: my mother’s family home that was located along the old Machida Route until the early Showa Period at the end of the 1930s. In the backyard of Narutoya, an indigo dye shop, the fabrics where dried in rows, each tied one pole to the other stretched with hundreds of thin bamboo pins to maintain the width of the fabric.

“400 Meter White Line” is a remake on paper of the “100 Meter Canvas” that was shown at the one-person show at the Pinar Gallery in Aoyama in 1971. The other works are a portion of the “Sengai Series.” The name of this series comes from my desire to transcend the predictable realm of awareness and to reach the territory that Sengai attained, to reach the outside the line (Sengai’s name and line outside is a homonym in Japanese) by appropriating the circle, triangle, and square painted by Sengai (1750-1835). This “Sengai Series” was begun around 1992. In the one-person show held that year in Osaka at the Kuranuki Gallery, I was inspired when I saw the work at the Idemitsu Art Museum located on the upper floor of the same building.

XII. Black Rain

In 2001, I began a project entitled “2001 in 2001” to create 2001 images celebrating the new century starting with the “Sengai Series.” With the concern about the issue of storage as the works were completed, I chose to use thin plywood. The name of the series changed to the “Monado Series” (monology) and then after visiting Hiroshima in 2007 to the “Black Rain” Series.” In this project, each of the works has the date and sequential number on the back. This project is yet to be completed. In the one-person show at the Machida City Tsurukawa Elementary School being held at the same time as this exhibition, the works that were made before and after the 9/11 are shown.

The “Black Rain” monoprints that hang from the ceiling attempts to go beyond the format of conventional printmaking by introducing one innovative manipulation in the process. The process is a simple one but at times can bring about unexpected results and excitement that is true only in the course of printmaking.

XIII. Machibi Series

5 banners, 90 centimeters in width and 10 meters in length, hang in the front hall of the museum. This is an attempt to utilize the instant communication means of banners with limited colors. Immediacy is the core of the visual arts and an important concept in my work. The clear and clean image of the banner has been used throughout history transcending different cultures to communicate identities.

My loft in Manhattan is located in Hell’s Kitchen, north of Chelsea and south of the Broadway Theater District. It is a part of the traditional Garment District where fabric and millenary stores, and wholesalers are located. In fact, my loft was previously a sweatshop, Paulette’s Undergarments. The fabrics for the banners were purchased in the neighborhood and created in celebration of this exhibition.

Keikando Gallery Project

The first exhibition ever held at the Keikando Gallery at Obirin University in Tokyo entitled “Hitoshi Nakazato: 55 Years Later” is a series of shows consisting of large-scale acrylic and oil works on canvas which opened on June 25, 2009. The third series began on April 1, 2010. The paintings in this show are works from the 1970s that were shown in the Contemporary Japanese Art Exhibition in Tokyo strongly influenced by conceptual art to those shown at the Tokyo Gallery, Muramatsu Gallery, and Hara Contemporary Art Museum through the 2000’s. Some of them have not been seen for 40 years. This series of shows have given me unexpected astonishment in hindsight and opportunity to see the breath of my own work in a new perspective.

I would like to acknowledge the Obirin art major students, faculty, and staff for making these exhibitions possible.

Hitoshi Nakazato

Translation: Sumiko Takeda/Editing: Gene Nakazato