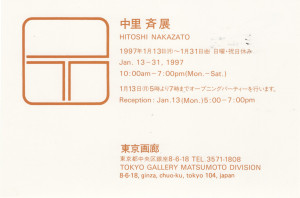

Hitoshi Nakazato Exhibition

Jan. 13 – 31, 1997

“… For more than two decades he [Hitoshi Nakazato] has assiduously worked and fused – perhaps one of only a very few artists to do so – two conflicting strains of abstraction: the pure retinal strategies of Color Field painting with the more cerebral, a systemic, endeavors of Conceptualism.

This has been Nakazato’s project since 1960s (so it comes as no surprise that he’s gotten so good at it). He has evolved a vocabulary of stripes, grids, boxes and bars in which the viewer is kept alert to every decision and brush stroke, every line and layer of color that has gone into making the painting. In his most recent paintings this intelligence is especially sharp and elegant as Nakazato has continued to refine and clarify both his means and his ends…

Nakazato is mischievous, devilish, delightful, light-handed, smart and affectionate. His is the spirit of abandon by way of graceful refinement. This series is truly a rhapsody: an optical, intellectual rhapsody to geometry, shape, color, lines and form, to figure-and-ground, to grid, to possibility, and more possibility. This series is a rhapsody to dual natures existing as one, to chaos and organization, to translucency, to porous, dusty color, to New York painting, to kimono, to the thoughtful and the decorative, to clouds and shadows of form, to air and earth and to the ecstasy of painting.”

Jerry Saltz, art critic

“The motif of the circle, triangle and square was chosen for the reason that these humanly derived shapes are such obvious clichés in Moderism. The extent to which this motif has been repeated verges on the ridiculous, and yet because of their obviousness, it fulfills my purpose. The decision to choose the obvious has been consistent in my work: the use of the line, the painting of the flat space between the lines in the earlier works, and more recently the use of the shapes and their distribution. …

The inspiration to use primary shapes occurred when I was preparing a show for the Kuranuki Gallery in Osaka, then located in the Idemitsu Building where the Idemitsu Museum is housed. The museum is noted for its collection of works by Sengai, the Zen artist/monk (1750 – 1838). Sengai’s is known for his simple brush drawing of the circle, triangle, and square in the middle of a horizontally oriented space. …

I decided to use the same motif, and named the series “Line Out Side” derived from a phonetic translation of the Chinese characters, Sengai. (Sengai actually means monk on a cliff.) By naming the series “Line Out-Side,” my intention is set my mind in a direction to ascertain that there is a wealth of possibilities outside what seems to be the accepted norm and to provide a line that would lead into the realm outside of the status quo. ”

Hitoshi Nakazato

- (left to right) Line Out-side ZN96, 1996; Gaistill LOSB, 1996; Line Outside, H. Diptych A, 1996

- (left to right) Line Outside, H. Diptych A, 1996; Line Out-side, sosoj, , 1996; Line Outside, meneji, acrylic on canvas, 1996

- 1997TG – (left to right) Line Out-side, H. Diptych B, 1996; Pistachio Green LOSM, 1995; Line Outside ZN96, 1996

- Left Yusuke Nakahara, art critic, Right Hitoshi Nakazato

- Right Tatsuo Kondo, artist

- Center Minoru Kawabata, artist

- Center Takeshi Matsumoto, Tokyo Gallery art dealer

Sensual Intelligence

The Recent Works of Hitoshi Nakazato

Hitoshi Nakazato’s painting is a revivalist art that resuscitates and breathes a fresh, new life into seminal styles of painting. Nakazato is a keeper of the faith, a true-believer in the communicative powers of abstract painting as a series of signs, as a vocabulary of forms and as a system of physical processes. He makes them newly legible and animated – talkative – so that they can speak with renewed vitality. Nakazato converts older ideas about abstraction and makes you feel like you’re looking at the dawn of something new; as if you are present at a genesis of form, the incubation of an idea and the bearing of some undulating, wavering fruit. Nakazato takes you on a journey from old to new; he makes painting a kind of aesthetic conversion – almost redemptive – like he’s shifting things around in order to reverse old ideas. He is particularly adept at the hybrid.

This is not surprising. As an artist born in Japan, who has lived in the United States for more than thirty years, Nakazato is himself a kind of cultural hybrid (He was schooled in Tokyo and then completed his Masters at the University of Wisconsin, and later attended the University of Pennsylvania where he studied with Piero Dorazio and Neil Welliver. He has shown internationally since the mid-1960s). He has the unique advantage of seeing the art world from both sides; from the inside and out. For more than two decades he has assiduously worked and fused – perhaps one of only a very few artists to do so – two conflicting strains of abstraction: the pure retinal strategies of Color Field painting with the more cerebral, a systemic, endeavors of Conceptualism. In other words he has combined the tradition represented by Kenneth Noland, Larry Zox and the very early Frank Stella with that of Dorthea Rockburne, Mel Bochner and Robert Mangold.

The goal of Nakazato’s beautifully colored, impeccably structured paintings seems to be a kind of sensuous intelligence, or an eroticism of looking or thinking – a kind of self-evident beauty whose attractions lie in its own making that also explains some of the most basic principles of painting: paintings as space, painting as field, painting as composition – as it goes. That may also explain the odd distance in Nakazato’s works. On the one hand it’s very smart work – you can see his thought process: he never covers his tracks. You can see exactly how the painting was made, which color came first, what covers what, and so on. But this also produces an uncanny intimacy; like you’re very, very close to him. This intangible emotional distance – or closeness – informs all of Nakazato’s churning, vacillating art, as every stroke, spasm, convulsion, every lurch of the brush is close at hand, and also ‘explained.’ Nothing is hidden in a Nakazato, yet nothing is also altogether revealed.

This has been Nakazato’s project since 1960s (so it comes as no surprise that he’s gotten so good at it). He has evolved a vocabulary of stripes, grids, boxes and bars in which the viewer is kept alert to every decision and brush stroke, every line and layer of color that has gone into making the painting. In his most recent paintings this intelligence is especially sharp and elegant as Nakazato has continued to refine and clarify both his means and his ends.

The new paintings lay out a language of forms: triangles, squares, semicircles, circles, wedges and notches balanced against a number of smudges, rough edges, brushy fields, blotchy lines and ethereal patches of metamorphic space. The layers of color can be filmy and thin, or inconsistent, vapor like, gaseous and gossamer. Or, and at the same time these fields of lush color can be solitary, prolonged meditations; persistent, rippling volumes. Space is flat or sometimes it bends. Distortion is subtle in a Nakazato. Mostly what you see is what is there, as everything is exposed. Executed with a sure, adept hand these paintings are a kind of internal balancing act (typical of Nakazato): urgent and thoughtful, unplanned and mapped out, ornamental yet straight forward (and unadorned), delicate yet solid, irregular but regular. Even the color feels wonderfully duel natured: sooty, smoky grays rest atop and caress open salmon pinks or a gorgeous orange does a dance with a slated gray; in another a dash of blue blurts into then floats across a field of velvety red-orange.

Over the years Nakazato has become a secret master of color, or an orator of color and rough edged connoisseur of it. He limits his color, there is no bombast – he’s not a show-off – no Expressionist ego; rather he exudes a sultry, sometimes quietly fierce sense of sexy color; unhampered by the need to impress you (his color is flamboyant but never dressed up; its dazzling without pomp). There is no other color in painting quite like Nakazato’s. The closest I can think of is the color and the texture of fabric. In any event, he knows these colors so well, by now, that they function like cloudy, succulent skins; artificial yet alive, charged with an intense need to see something simple and still beautiful, rudimentary yet ultimately reasoned. These colors are rarefied and chimerical yet they are so everyday that you might overlook their splendor.

This is a terrific in between scale to this series of paintings. They stand about 200 cm. But, because there is such a smooth uniformity of thought mixed with these now-and-then, here-and-there jumble of shapes, the works end up feeling incredibly human in scale. You can connect the paintings. This in between scale also harks back to the cusp of styles Nakazato seeks to bridge. He knows, in his bones, the large scale of the graspable, the ascertainable and the known. This is important because the scale, like his use of color, permits him to suggest a vast unknowable space and time, while keeping the paintings down to Earth, and about things that can be known.

Is it because he was born in Japan, or is it something innate, that makes these paintings feel like kimonos? You could wrap yourself in them, they seem reassuring that way; shelter like, protective and, again, sexy. And they are fantastically ornate without being frivolous. Each painting seems to possess a key to itself, but every painting unlocks something in the other as well. You get the feeling that not only is one voice speaking but a kind of duet of thought and second thoughts. There is this self-effacing quality to the work, but then, when you’re not thinking about it, or paying much attention, Nakazato – the painter – is there, in your face, right in front of you – and he’s kind of confrontational. That’s when you feel his full strength and power. His skill is considerable, and when you focus on it can be a little intimidating – but the individual work, as well as the series, is spiced with a mysterious modesty and mute exuberance. There is no absolute pattern, no real symmetry; all the same there is a logic to it. It makes you feel in touch with something wildly organized, yet all together chaotic and arbitrary.

There is also a connection to more distant art: to modernism, itself. Nakazato’s edges are alive with vibrant, back-and-forth energy – almost electric – popping, and call to mind the areas, in a Mondrian, where one color crosses over another and produces a hot spot or flash. Mondrian’s edges, however, are labored, meticulous things – slower than Nakazato’s, but a lot happens there. Also Nakazato’s colors are more complex than Mondrian’s blacks, whites and primaries. Nakazato’s sense of spacing – how he moves shape and spaces across a canvas – also connects up to Stuart Davis. Interestingly, Davis also bridges several styles to create his own.

A spirit of reverie inhabits these paintings; an aspiration that silently filled the whole series is played out for all to see. Nakazato is mischievous, devilish, delightful, light-handed, smart and affectionate. His is the spirit of abandon by way of graceful refinement. This series is truly a rhapsody: an optical, intellectual rhapsody to geometry, shape, color, lines and form, to figure-and-ground, to grid, to possibility, and more possibility. This series is a rhapsody to dual natures existing as one, to chaos and organization, to translucency, to porous, dusty color, to New York painting, to kimono, to the thoughtful and the decorative, to clouds and shadows of form, to air and earth and to the ecstasy of painting.

Jerry Saltz is an art critic who lives in New York and is a contributing editor to Art in America and Art Auction.

Meditations on the Line-Outside

The motif of the circle, triangle, and square was chosen for the reason that these humanly derived shapes are such obvious clichés in Modernism. The extent to which this motif has been repeated verges on the ridiculous, and yet because of their obviousness, it fulfills my purpose. The decision to choose the obvious has been consistent in my work, the use of the line and the painting of the flat space between the lines in the earlier works, and more recently the use of the shapes and their distribution. My painterly intention is not the discovery or introduction of new images as can be seen in the historical context of art, whether it is derived from the outside world, or inside one’s mind. Then, how do I accomplish the task I have undertaken in imagemaking? The painterly issue is the fusion of, or the attempt to deal with, what may be considered the conflict between the attitude of denial toward the norm in picturemaking and the desire to paint.

The inspiration to use primary shapes occurred when I was preparing a show for the Kuranuki Gallery in Osaka, then located in the Idemitsu Building where the Idemitsu Museum is housed. The museum is noted for its collection of works by Sengai, the artist/monk (1750 – 1835). Sengai is known for his simple brush drawing of a circle, triangle, and square in the middle of a horizontally oriented space. Although the exact date of the work is not known, there is no doubt that it was executed more than a hundred years ago, preceding the advent of Western Modernism. How Sengai came up with this imagery, so unlike his time, remains a mystery to me.

I decided to use the same motif, and name the series “Line Out-Side” derived from a phonetic pronunciation of the Chinese character, Sengai. (Sengai actually means a monk on cliff.) By naming the series “Line Out-Side,” my intention is to set my mind in a direction to ascertain the wealth of possibilities outside what seems to be the accepted norm, and to provide a line that would lead into the realm outside of the status quo.

More than ever before in this day and age, Modernism in a sense dictates a philosophy that effects art and its thought process that makes foremost the need for painters to come to terms with ‘what’ they should or should not paint, followed by ‘why’ they chose to choose ‘what’ they chose. The means or the ‘how’ to go about implementing the ‘what’ and ‘why’ closely follows suit. However, within the creative process, the order of this process may very well shift and change in a state of flux. The process of painting the large field with the colors of my choosing excite me. As I paint the ground rather than the shapes themselves over the other color, the shapes begin to emerge and the configuration of the images develops on the canvas.

I was motivated to play with the use of brush strokes this time, to shed the restraints I had imposed upon myself previously as a should not. My thought as I write this is that if I can reach the state of mind that Sengai was in when he drew the one large circle in the middle of the field with the inscription, “Eat this and drink tea.” I will have reached a state of the sublime, free of constraints.

Hitoshi Nakazato

January 1997, New York