Hitoshi Nakazato Exhibition

June 23 – July 5, 1986

“But the successive metamorphoses in Nakazato’s art during the past decade also reveal that he has never been satisfied with mere virtuoso display of seductive craftsmanship, either of which would have a lesser artist in fatal repetition. For Nakazato thinks on two levels simultaneously, the first that of the many ways of achieving a goal, and the second that of the goal itself. Thus the animating power of line upon canvas was followed by his awareness that line also creates areas of color which, when put into a certain relation both to each other and to the structure of lines that engendered them, will bring forth out of canvas a new and more complex, yet unified, visual intensity.”

Edward F. Fry 1986

Former Associate Curator of Guggenheim Museum, Co-director of the 8th Documenta (Kassel, Germany) 1987

-

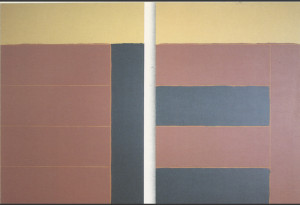

Coe

Oil + acrylic 214 cm X 173 cm (each)

1985

-

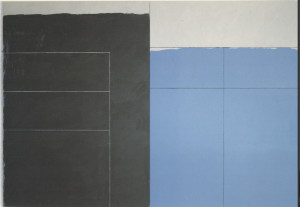

Maas

Oil + acrylic 214 cm X 306 cm

1985

Hitoshi Nakazato Exhibition

When I first saw the work of Hitoshi Nakazato more than 15 years ago, before he was awarded a major prize at the 1971 Japan Arts Festival at the Guggenheim Museum, I knew instantly that I was in the presence of a supremely gifted artist and a unique talent: Someone who, with the slightest and apparently effortless feathering of line upon canvas, could bring forth out of painting a sonorous polyphony of pure visual intensity and feeling. It is this rare gift, of charging into a rectangular, flat canvas with passionate subtleties of mind and emotion, which Nakazato has continued to reveal throughout the 1970’s and to the present day.

But the successive metamorphoses in Nakazato’s art during the past decade also reveal that he has never been satisfied with mere virtuoso display of seductive craftsmanship, either of which would have a lesser artist in fatal repetition. For Nakazato thinks on two levels simultaneously, the first that of the many ways of achieving a goal, and the second that of the goal itself. Thus the animating power of line upon canvas was followed by his awareness that line also creates areas of color which, when put into a certain relation both to each other and to the structure of lines that engendered them, will bring forth out of canvas a new and more complex, yet unified, visual intensity.

To my Western eyes, which are nevertheless not completely innocent of Japanese traditions, Nakazato’s art possesses a further dimension, of the highest interest, in its dialectical response to both modern American esthetics and traditional Japanese forms, be they of emblems, the tatami, or the visual/intellectual synthesis of the challigraphic character itself. For Nakazato brings to modern Western esthetics, especially to its emphasis on the emotive, symbolic possibilities available to western abstraction; but at the same time, Japanese tradition is also recast into a new and transformed version of itself.

The result is these extraordinary paintings, which are both western and Japanese, old and new, and which make us aware of the two intersecting traditions from which they arise; far more aware than if we had remained safely, and unconsciously, within either tradition alone. Nakazato’s works are therefore metaphors, ideograms of doubly liberating self-consciousness and enlightenment which are granted to us by rarely in this life, but which this artist offers freely as his gift to the world.

Edward F. Fry

Philadelphia/New York, May 1986