Hitoshi Nakazato Exhibition

Nov. 1 – 20, 1993

“So, what are these paintings all about? The necessary things for what is proverbially known as an “expression” are voluntarily and entirely abandoned. Therefore, it is anti-expressionism. From the works of the 60’s to the new works in the 90’s, this approach exists throughout Nakazato’s work…

… The manner in which Nakazato creates images based on the given physicality is a task which painting returned to the conceptual level of innocence, after which images are then added as not to impair the state of innocence to extricate the physicality, which is the canvas, the aspect of semblance itself.”

Tasumi Shinoda, Japanese art critic (1951-)

-

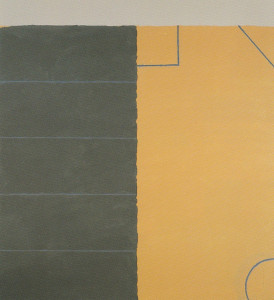

Stairs at Quai,

White/Yellow Line Oil + Acrylic on Cotton

224cm X 221cm

1993

-

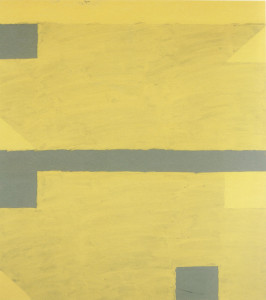

Vkhutein Courtyard, Gray/Yellow

Oil + Acrylic on Cotton

224cm X 198cm

1993

-

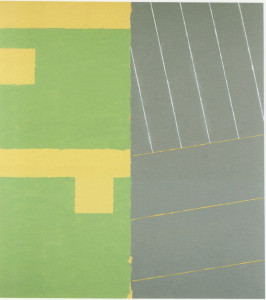

Vakhtan Wood Pile, Green/Yellow

Oil + Acrylic on Cotton

224cm X 221cm

1993

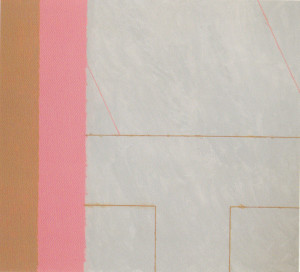

- Sanyata within Brown/Gray/Pink 1993 Oil, acrylic on cotton canvas 244cm X 221 cm

- Line Outside with Three Shapes 1993 Oil, acrylic on cotton canvas 244cm X 221 cm

The State of Innocent and the Aspect of Sign

Could there be a painting that is free from paintings? If there is, it could be the work of Hitoshi Nakazato of which I am about to write.

To search for any meaning in the forms that appear in Nakazato’s painting is impossible. There would be no answers to the questions for those who seek meaning in the rectangles, squares, and triangles that are created by partitioning. Therefore, in order to respond to the question of why the paintings are composed of forms that do not convey meaning, the observer must pursue to understand and solve the painting.

The same can be said about the lines and colors. No, that may not be the case. The nature of the lines themselves are for the most part evenly drawn. It is not only that the lines are straight, but the pressure on the lines are regular. These lines with their self-imposed movement would never induce any change in human emotions. Yet, that is not to say that there is no nuance. Therefore, they can not all be called lines that do not transmit emotion. Nevertheless, there is the need to know the reason behind their evenness.

Color evoke emotions more easily, yet despite the different colors in the works, the emotion (whether or not emotion exist is subtle and that may perhaps relate to the chroma) that each painting transmits can not be said to be different. In other words, as the chroma is evenly applied, the overall chroma which is somewhat lower in the new works in comparison to earlier works, and the strength of emotion whether it subtlety exist or not, is transmitted also so that there is no definite difference. As a result, it is only possible to deduce that color itself is not of importance, and not aimed to transmit emotion.

Further, let us take a look to see how color is used in any one of the works. Is there one work in which one particular color is predominant and expresses the intent of the painting? In other words, is there a work which might convince the viewer that the color should really be the issue?

In the works which are vertically divided into half, the colors seem adverse against the other color becoming dominant over the other within the canvas. This is the means for self control not to give the picture emotional content. Among the shapes, there are no shapes that stand out to determine an impression for the work.

The value of color is balanced diligently. The value and area of color are carefully planned in order not to create the tier of tonal gradation, in effect, not to provide an area that is emphasized and the other not. The evenness of chroma is definitely the egalitarianism of color according to the character of the color. Therefore, the nuance of the brushstrokes on the surface is not aimed to transmit emotion either, but can be seen as a device to uphold this egalitarianism.

So, what are these paintings all about? The necessary things for what is proverbially known as “expression” are voluntarily and entirely abandoned. Therefore, it is anti-expression. From the works of the 60’s to the new works in the 90’s, this approach exists throughout Nakazato’s work. What is Hitoshi Nakazato trying to incorporate in his paintings?

Before incorporating any elements, he is eliminating them, the magic of color, movement of line, and indefinite changes of form about which everyone knows. And they also know how much these elements can be of detriment to paintings. Yet, such paintings are still probably and continuously troubled by self-complacency of color, line, and form. So, how about eliminating all of them, if that can be done? By doing so, couldn’t painting be returned to lightness and sinlessness, to the state of innocence?

Perhaps, if there is a painter closest in approach to Hitoshi Nakazato, it would have to be Cy Twombly. The issue that Twombly has been dealing with in his paintings by using graffiti-like lines is to distances himself from “expression.” He has shed the “line as expression” with the graffiti-like line, freed his work from the spell of form, and cast off the history of color magic. The true issue in Twombly’s work does not exist in the geste of ecriture as Roland Barthes has pointed out, but can be considered to exist in the shedding of painting from paintings.

Therefore, in the successful works of Twombly, the impression of extricating itself from something and becoming the semblance of “the image” itself teaches the viewer that the picture by this artist is the picture about the image of painting. And Nakazato’s paintings, also, is the same way. Although the shedding method is different, the picture is returned to the state of innocence. And in the manner of grasping the “image of painting” for the aspect of semblance, which may or may not exists, both the works of Twombly and Nakazato whisper to one another.

Accordingly, Nakazato is not interested in painting the basic forms. The painted forms are always executed in reference to the painterly physical, given, condition of the canvas. The vertical and horizontal elements are images based and evolved merely from the canvas edge. The diagonal lines and the assemblage elements of the diagonal lines, too, are basically the referential aspect to the grit structure that paintings possess physically, and not an expression of something.

What is subtle here in my perception is that these measures are not taken to bring objectivity and physicality to painting. These solemn words, objectivity and physicality, become oppressive by categorizing artists’ works as Minimalism or Conceptual Art, creating many misunderstandings. The manner in which Nakazato creates images based on the given physicality is a task in which painting returned to the conceptual level of innocence, after which images are then added as not to impair the state of innocence to extricate the physicality, which is the canvas, to the aspect of semblance itself.

In order to make the painting viewable, there is a need for a concept and that is what this is all about. Nakazato’s work, based on the definition that Cy Twombly’s works are Conceptual, or else, on the definition that all great works of art make conceptual inquiry possible, and in a dimension that is unrelated to isms, is already conceptual.

The titles of the new 1993 works were given after Nakazato happened to notice the photos of Rodchenko in which a man carries wood on his shoulder in a lumber yard and tied the idea into this show which is to take place at Shinkiba, literally meaning new wood place. So, the photo of a lumber yard is related to the title “Vaktan Wood Pile”, the photo of a person climbing steps to “Stairs at Quai”, and the photo of a blind alley with irregularly lined houses to “Vkhutein Countyard”. These titles may or may not denote function, as they would only evokes a reaction from people who are familiar with Rodchenko. Therefore, it is clear that the title is not important.

The same can be said for the other titles, for instance, the Sanskrit word “Sanyata” means color and sexuality at the same time and present the Eastern thought of sensation toward color, and “Line Out-Side” is “sengai”, the homonym for “Sengai” a Zen priest. If there is meaning in the choice of these titles which do not seem to be an important issue, it can not be considered but an attempt to denote the instructional function or content reaction from without.

This has a similar relation to Nakazato’s process in which the image is derived from the given condition of physical property, the rectangle and the edge of the canvas. In order for the painting to resist falling into self-righteousness that the artist’s emotion and sensation create in the meaning and imagery, he introduces “das moment” of externality. The titles given is one aspect of this.

Therefore, the fact that the series from 1987 were created in the loft with the television broadcasting the Iran Contra Hearings is reflected in the titles, and the fact that the multi-panelled large-canvas works of this series have companion pieces attached or independently exist next to them, is considered as parallel to the introduction of external “das moment.” That is the variation of “das moment” which is rooted in a kind of conceptuality that a painting freed from paintings inevitably has within. So expression and construction do existed in the different dimensions from the beginning.

Hence, the conceptuality reached after considerations within painting to shed all excess, may relate to the aspect of “sign.” It is possible to conclude, therefore, that the aspect of sign that exists in reductional painting, including Nakazato’s work, share a common bond with Conceptual Art that is based in the dominance of concept, and Color Field Painting that places importance on visuality and sensation. This aspect of sign may very well related to Nakazato’s recent concern for the Russian Avant Garde and his concern by his words, “paintings that are not paintings.”

The relationship between the aspect of sign and the Russian Avant Garde is not clear in Nakazato’s work, but by extending imagination through the issue of iconography in Malevich’s paintings, Italian fresco paintings which have always been a part of Nakazato’s interest come to mind. And from the point of view of paintings in a state of innocence, that has not accumulated the weight of painting, there is none other than the Italian paintings of the 13th and 14th century that reminds us of this state. This could be the reason why Cy Twombly now lives in Italy.

Hitoshi Nakazato creates space for these reborn child-like paintings that have been reductionalized to the state of innocence. His issues are more important and applicable to all paintings rather than the specific issues of American paintings or Japanese culture.

Tatsumi Shinoda

Translation: Sumiko Takeda